I confess I’m addicted to booklists. No sooner do I finish one book, but I’m into another.

What surprises me is that I can’t remember anyone in my family serving as a role model when I was a child, either reading to me or picking-up a book for themselves, with the exception of the late intervention of my eldest brother, David, recently discharged from the army after WWII and anticipating college under the newly inaugurated GI Bill.

One night before David left for the University of Miami, he gave me my first book, Huckleberry Finn. I still remember the occasion–eight years old, sprawled out on the floor of our Philly tenement, absorbed so fully in this really good book that it muffled the adjacent Front Street el with its interminable trains, dutifully groaning past our rattling windows every fifteen minutes.

Soon I discovered the Montgomery County Library. I didn’t mind walking the two miles, knowing what lay up ahead. It was one of those supreme pleasures like feasting on a well-stacked hoagie or downing a cold strawberry ice cream soda on humid summer Philly nights; maybe I even liked it as much as playing stick ball every day against the factory facades lining our streets.

Books gave me refuge in a home torn apart by alcohol. I became aware of a larger world, where good really did exist, and people could be kind and often courageous. I found heroes like Lincoln, Gandhi, and Gehrig that would become staples in my life. Books transported me to far away places—Australia, New Zealand, the South Pacific.

Nearly as important as the library was a humble bookstore on Girard Avenue that I often passed on my way home from Chandler Elementary, filled with used paperbacks. What got my attention were two cardboard boxes piled high with comic books. I gravitated to the one filled with Classic Comics with their graphic renditions and abridged texts of literary fare. The price, five cents, sealed the bargain! I’d “picture” my way through, say, Les Miserables or Treasure Island, then pick-up the hardback version at the library. By the time I was 13, I had read many of the classics, including War and Peace, Moby Dick, and Silas Marner.

As for the many booklists I’ve ransacked through the years to feed my addiction, I’ll just say my favorite has been Brain Pickings, whose cerebral fiber fences it off from the traffic lane of your typical booklist..

For the most part, I shun the New York Times best seller lists, annoyed by their often fad offerings of dubious value other than to entertain or tell how you, too, can cash in and grow healthy, wealthy and wise. A few weeks later, I’d find these books either gone awol or sunk to near oblivion.

Before the Internet opened up our information corridors, I’d reminisce earlier times venturing into a library, losing myself in its stacks, often looking for one book, but emerging with another. Call it serendipity, but the chance encounters I’ve had with library books have often proved fortuitous with surprising consequences.

Take, for instance, one chance venture when I pulled a book off the shelf by an author I’d never heard of. Lucky draw, it turned out to be Thomas Wolfe and his Look Homeward Angel. I was 17 at the time, a homesick GI in Korea resorting to the humble base library to annul slow time. Hooked, in subsequent years I rampaged all of his novels, ultimately enrolling at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the Pulpit Hill of Look Homeward Angel.

Books often haunt my mind, ghosts of delightful company with motley heroes, or of vistas spinning new threads of excitement, belief, and desire in conspiracy against the old.

But I’ve found that even the Internet can surprise me. Several days ago, for example, I stumbled upon an extended New York Times Style Magazine series, “My 10 Favorite Books,” edited by Aaron Hicklin.

Hicklin edits a magazine called Out and recently opened up a bookstore called One Grand Books in Narrowsburg, NY. In a clever ploy to attract readers, he’s come up with the idea of asking well-regarded people from various walks of life what ten books they’d want to have with them were they marooned on a desert island. Each listing would feature annotated entries explaining their choices or how these books came to shape their lives.

Hicklin doesn’t want just another bookshop, a dubious business venture in this age of online behemoths like Amazon and Barnes & Noble, but a resource for discriminating readers to find books of substance readily.

As I write, contributors to “My 10 Favorite Books” include, among many others,

What’s nifty here is how when you select a contributor you get a cascading menu of ten annotated preferences. In short, each menu constitutes a sub-booklist in the series. Amazingly, very little overlap occurs among contributor choices, yet each listing is profoundly discriminating.

Absent from the list are two writers I’m unfamiliar who intrigue me for their choices, since they complement my own interests–artist Terence Koh and author, Brett Easton Ellis–the former for his love of Eastern thought with its subdued nuances in a sound byte world; the latter, in sharing tastebuds with me for writers like Tolstoy and Flaubert.

Hicklin, by the way, keeps an online blog, onegrandbooks, that provides you with an archive of previous contributors and a weekly focus on a current contributor, sparing you the cumbersome difficulty of finding each series individually online. You can even sign-up for his weekly newsletter and have your purchased item shipped conveniently to your doorstep.

I hope Hicklin’s venture succeeds. It’s a brave new world out there

Meanwhile, I’m on safari, exploring panoramas of infinite sweep_better because unanticipated, by way of my new booklist quarry.

–rj

I’ve been keeping my blog, Brimmings, for five years now, never realizing when I began that I would pursue it for so long, initially undertaking it to assuage my wrestlings with serious illness at the time, or as diversion from anxious self-preoccupation, for liberating reflection of a wider scope. When we let loose our moorings, we sail into discovery.

I’ve been keeping my blog, Brimmings, for five years now, never realizing when I began that I would pursue it for so long, initially undertaking it to assuage my wrestlings with serious illness at the time, or as diversion from anxious self-preoccupation, for liberating reflection of a wider scope. When we let loose our moorings, we sail into discovery.

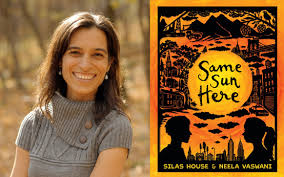

My thirst for good reads continued in 2015, and among them, two stand out for special praise in providing me with pleasure, insight, and continuing reflection. (I’ve reviewed both more fully elsewhere in Brimmings.)

My thirst for good reads continued in 2015, and among them, two stand out for special praise in providing me with pleasure, insight, and continuing reflection. (I’ve reviewed both more fully elsewhere in Brimmings.) Non-Fiction: Oliver Sacks: On the Move: A Life

Non-Fiction: Oliver Sacks: On the Move: A Life