I woke up at 4 a.m. this morning, dawn’s light still absent, an annoying habit of mine, worsened by turning-in too late, despite ardent resolve to do better. God knows, I need more than four hours of sleep, and I pay for it, drifting off repeatedly as day unfolds.

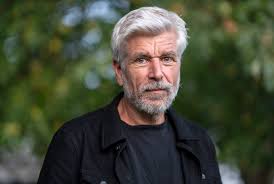

To cope, I try teasing myself back to slumber—whatever works—like counting up to 100 in Italian, gleaned from daily Italian lessons. Or better, groping for the iPad beside me to resume my daylight read, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s massive My Struggle, despite blue light barriers to sleeping well.

I read a lot—mainly books I often list in Brimmings each New Year’s Day. Right now, I’m deep into Book Two of My Struggle, part of a six-volume series totaling nearly 3,600 pages—or three times the length of War and Peace. In contemporary writing, only Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels, at roughly 2,000 pages, come close in length. (Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past runs to 3000 pages across seven volumes.)

Overall, Book Two details Knausgaard’s move to Sweden, his family life with second wife, Linda, and their three children; the tensions arising from his obligations to family life and dedication to writing:

Now I had everything I had dreamed of having since I was a teenager: a family, a wife, children—yet none of it made me happy. On the contrary, I was constantly on the verge of tears, I was always angry, always tired.”

The love I had for Linda was not stable and warm but consuming and often destructive.

I’m attempting all six volumes. I wonder how many have done this and for what reasons. My guess is very few have climbed the mountain, but I’m liking the climb.

In his penchant for recalling past event, interspersed with personal reflection narrated over several volumes, Knausgaard has often been compared with Marcel Proust.

While his prose may lack Proust’s lyricism, it compensates with acute playback of places lived, voices heard, and life’s everyday ironies. It’s like he’s sitting across from you, filling the room, talking to you directly.

Though he’s won several Scandinavian literary awards, he’s yet to take home a prestigious International Booker translation prize or Nobel.

Writing in Norwegian hasn’t helped. There are only 5.5 million Norwegians. It’s the uphill climb all non-English writers face in an industry still dominated by native Anglophones. And so I commend The New York Review of Books for its continued effort to revive works originally not written in English.

Some critics think Knausgaard narcissistic for his self-focus, but they forget: he’s writing memoir. Anyway, when is writing anything but a quest to be heard or validated? I think they’re being simplistic.

In Norway, readers were shocked at Knausgaard’s inclusion of family and friends, names unchanged, intimate details not held back. An uncle threatened to sue and former wife, Linda, suffered mental distress, requiring therapy.

Knausgaard can make anyone uncomfortable. He doesn’t hold back about life’s often brutal truths. But to me, that’s his strength. I like writers who unflinchingly deliver human experience.

Knausgaard writes what’s known as autofiction, a blurring of the distinction between the factual and the fictional. Memory, subject to filtering, is unreliable. We cannot even say we fully know ourselves. By this yardstick, even autobiography becomes an act of arbitrary inventory—selecting, omitting, fabricating—and, hence, approximates fiction, or as Knausgaard puts it, memory “is not a reliable quantity in life” as it “doesn’t prioritise the truth, but rather self-interest.”

I admire his directness and minute detail. I revel in his feel for nature’s splendors, vignettes of people and their eccentricities, the fiery fever of first love; thoughts on today’s politics, obsessions imposing self-censure, the ennui often accompanying contemporary existence, and not least, the myriad burdens of the writer’s life.

I always longed to be away from it. So the life I led was not my own. I tried to make it mine, this was my struggle, because of course I wanted it, but I failed, the longing for something else undermined all my efforts.

The foregoing passage helps explain the series title, My Struggle, with its provocative echoes of Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Knausgaard’s struggle, however, is an existential one—that of locating oneself in a world often hostile to individuality, of finding balance between writing and family, each under pressure of cultural conformity.

…perhaps it was the prefabricated nature of the days in this world I was reacting to, the rails of routine we followed, which made everything so predictable that we had to invest in entertainment to feel any hint of intensity?

Knausgaard’s critique of cultural homogenization, creeping across Europe like some unchecked fungus, especially resonates with me:

There was the revulsion I felt based on the sameness that was spreading through the world and making everything smaller? If you traveled through Norway now you saw the same everywhere. The same roads, the same houses, the same gas stations, the same shops. As late as the sixties you could see how local culture changed as you drove through Gudbrandsdalen, for example, the strange black timber buildings, so pure and somber, which were now encapsulated as small museums in a culture that was no different from the one you had left or the one you were going to. And Europe, which was merging more and more into one large, homogeneous country. The same, the same, everything was the same.

Thoughts arise of a visit to Moscow’s Red Square with my students, of fast-food chains—TGI Friday’s, McDonald’s, Pizza Hut, KFC—littering its periphery, exporting America’s consumer culture and eroding local identity; memories of a journey to France—a student lamenting time and money visiting Europe, only to find blue jeans, blaring American music, and global brands echoing home.

There ‘s a humility clinging to Knausgaard’s narrative, a confessed reticence to assert himself in a society indifferent and perhaps judgmental in its appraisal of those differing from the norm:

I subordinated myself, almost to the verge of self-effacement; some uncontrollable internal mechanism caused me to put their thoughts and opinions before mine.

I saw myself as the weak, trammeled man I was, who lived his life in the world of words.

My Struggle abounds in quotable reflections that I hasten to underscore like this hauntingly melancholic passage, evoking a past where dignity, nature, and artistry coexisted—however harsh the drawbacks of its era:

…if there was a world I turned to in my mind, it was that of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with its enormous forests, its sailing ships and horse-drawn carts, its windmills and castles, its monasteries and small towns, its painters and thinkers, explorers and inventors, priests and drugstores. What would it have been like to live in a world where everything was made from the power of your hands, the wind, or the water? What would it have been like to live in a world where the American Indians still lived their lives in peace? Where that life was an actual possibility? Where Africa was unconquered? Where darkness came with the sunset and light with the sunrise? Where there were too few humans and their tools were too rudimentary to have any effect on animal stocks, let alone wipe them out? Where you could not travel from one place to another without exerting yourself, and a comfortable life was something only the rich could afford, where the sea was full of whales, the forests full of bears and wolves, and there were still countries that were so alien no adventure story could do them justice, such as China, to which a voyage not only took several months and was the prerogative of only a tiny minority of sailors and traders, but was also fraught with danger. Admittedly, that world was rough and wretched, filthy and ravaged with sickness, drunken and ignorant, full of pain, low life expectancy and rampant superstition, but it produced the greatest writer, Shakespeare, the greatest painter, Rembrandt, the greatest scientist, Newton, all still unsurpassed in their fields, and how can it be that this period achieved this wealth? Was it because death was closer and life was starker as a result? Who knows?

Knausgaard has this way of arresting you mid-thought and making you reassess your values.

Book 2 emphasizes the fissure between the expected of you and living your true self. For writers living in a world of the utilitarian with its compromises, the challenge of finding equilibrium can be daunting :

To write is to carve a path through the wilderness. It is to find something that has not been said before, something you can believe in, something that gives meaning to your life.

Again, the unstinting honesty, whether commenting on contemporary mores, engaging in philosophic reflection, or offering informed opinion separating the trivial from the significant.

They say Book 6, 1000 pages long, is steep in philosophical reflection. Whatever, I look forward to the climb.

The New Yorker critic James Wood praises Knausgaard’s ability to extract the profound from the mundane as “hypnotically compelling.”

The Atlantic’s William Deresiewicz applauds Knausgaard’s philosophical depth as a “contemporary Proustian endeavor.”

Life is never simple for Knausgaard in his dense weave of mystery and randomness, of inheritance and free will, of human frailty and moral striving..

I find that compelling.

And so, even when I awake, the silent stars my sole companions, I find pleasure in his company, a friend to see me through the night.

–rj