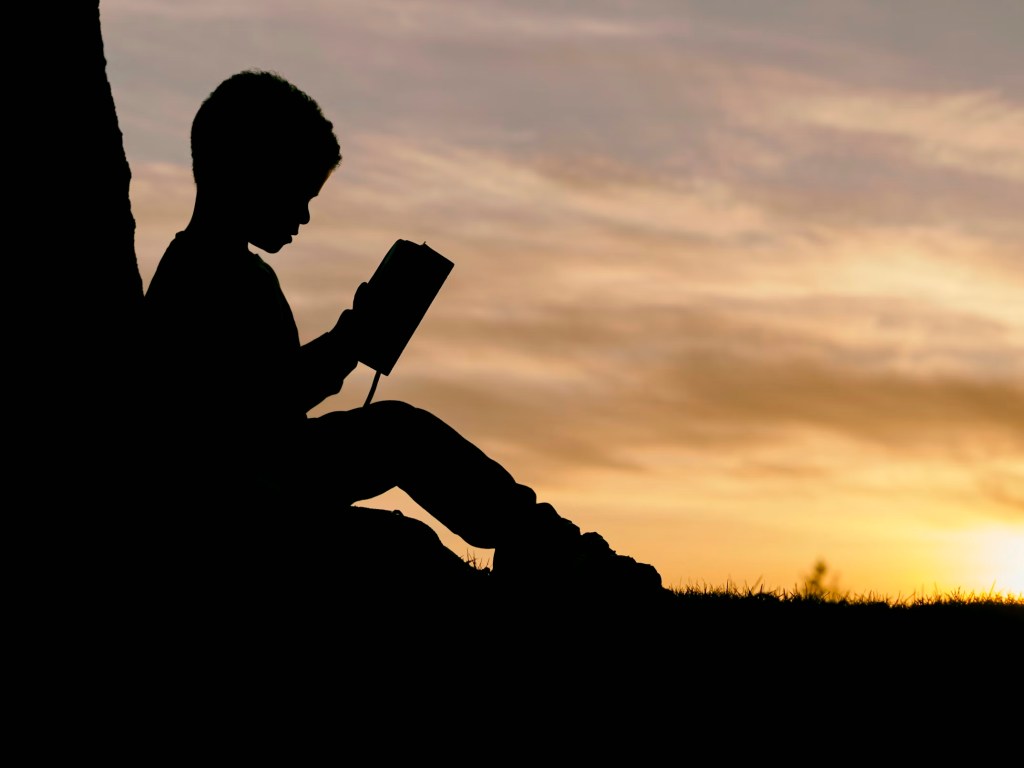

My fierce love for books has its ancient beginnings as a seven year old, sprawled on a Philly tenement floor, enthralled with a Christmas gift, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

Moments ago I rediscovered this passage from France’s Michel Houellebecq, who has this special capacity to rattle the cages of accepted opinion—daring, provocative, forthright—writing novels you simply don’t walk away from.

I had read his Submission several years ago, an initial novel that launched his fame. His take on literature, a dying indulgence in a digital age, is poignant with meaning for me, for literature has surely been among life’s greatest gifts to me:

“…the special thing about literature, the major art form of a Western civilization now ending before our very eyes, is not hard to define. Like literature, music can overwhelm you with sudden emotion, can move you to absolute sorrow or ecstasy; like literature, painting has the power to astonish, and to make you see the world through fresh eyes. But only literature can put you in touch with another human spirit, as a whole, with all its weaknesses and grandeurs, its limitations, its pettinesses, its obsessions, its beliefs; with whatever it finds moving, interesting, exciting, or repugnant. Only literature can grant you access to a spirit from beyond the grave—a more direct, more complete, deeper access than you’d have in conversation with a friend” (Submission).

I have not found a more eloquent articulation of my own passion for literature and think often of what I would have missed had I not been introduced to literary reads—above all, to see past the literal text and be transported into a galaxy of resonance where words could mean beyond themselves, open new vistas, shaping life, capable of numinosity, a sense that life exceeds appearances, infinite in its labyrinthian corridors, a non-ending conversation with what is, has been, and will endure.