I’ve been absent from Brimmings for nearly a week, recovering from a serious bout with the flu—the fever lingering for ten days. A chronic cough remains my daily companion.

That hasn’t stopped me from reading—slowly, attentively—six books already this year.

As I’ve previously shared, alongside my annual eclectic reading list, I’ve committed to a topical approach to reading as a way of resisting intellectual grazing and cultivating sustained attention (Topical Reading). I’ve begun with Kentucky sage Wendell Berry, now in his ninety-second year.

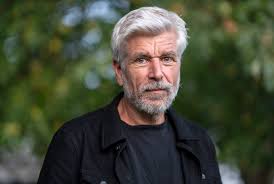

I didn’t want to one day come upon his obituary and feel the guilt pangs of having neglected an agrarian pacifist, a champion of the local, often described, without much exaggeration, as America’s “moral conscience.”

Berry has farmed a 125-acre hilly tract adjacent to the Ohio River at Port Royal in Henry County, Kentucky, for more than forty years. Farming, for him, is not metaphor but moral practice. As he writes, “The care of the Earth is our most ancient and most worthy, and after all our most pleasing responsibility.”

Academically, Berry is no lightweight: a BA and MA in English from the University of Kentucky, a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford, and a Guggenheim that took him to Italy, he taught briefly at New York University before returning—against the counsel of colleagues who believed he was jettisoning a promising academic career—to rural Kentucky and the family farm.

They were wrong.

Berry has since written more than fifty books spanning essays, novels, and poetry. His great theme is stewardship—not management or control, but reverent care. “The idea that people have a right to an economy that destroys nature is a contradiction,” he writes, insisting that economic life must answer to ecological reality.

For the farmer Berry, stewardship begins with the soil: an antipathy to chemicals, a reverencing of the biosphere, and a life lived according to natural rhythms. He is deeply opposed to industrial agriculture, which he regards as a cultural as well as ecological calamity: “Industrial agriculture is not just bad for farmers; it is bad for land, for rural communities, and ultimately for culture.”

Among American environmental writings, the two most salient works I’ve encountered are Thoreau’s Walden (1854) and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962). Thoreau’s aphoristic brilliance lends itself to endless quotation: “Our life is frittered away by detail… Simplify, simplify,” while Carson’s prose approaches poetry. Her opening paragraphs of Silent Spring remain, to my mind, the finest in environmental literature, exposing the arrogance behind what she called “the control of nature, a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy.”

I’m only in the early stages of getting acquainted with Berry, but he keeps distinguished company with Thoreau and Carson in his passion for preserving nature’s bounty and the pulchritude of a simplified life lived in fidelity to place and community.

In this sense, Berry reaches back to Thomas Jefferson, whom he quotes more than any other figure: “In my own politics and economics I am Jeffersonian.” Jefferson believed liberty was best secured in small, decentralized communities of independent producers, warning that distant power—whether governmental or economic—inevitably corrodes responsibility and freedom.

Though Berry was an activist who vehemently opposed the Vietnam War and has voted Democratic, his politics resist easy classification. He has lamented that America’s two major parties have grown increasingly to resemble one another.

There may appear, at first glance, to be overlap with libertarianism—his opposition to big government, military expansion, and imperial intervention—but the resemblance is superficial. Libertarianism exalts the autonomous individual; Berry emphasizes communal obligation. “We do not have to sacrifice our economic well-being in order to act responsibly toward our land and our neighbors,” he writes. “Rather, we must do so in order to preserve our economic well-being.”

Berry has his critics. His suspicion of technology strikes some as untenable in a hungry, overpopulated world. Can an aggregate of small family farms feed a wired and burgeoning global population, particularly in parts of Africa?

I find myself grappling with his apparent parochialism. Only a tiny fraction of Americans now farm. What of the rest of us who earn our livelihoods elsewhere? And in an interconnected age, can the local truly stand apart from the global?

Berry would respond that the issue is not technology itself, but dependence. “There is a difference between being technologically advanced and being technologically dependent,” he reminds us—a distinction too often elided in contemporary debates.

Ironically, Berry would fit comfortably in an Amish community. He still plows with horses. He owns no computer, television, or mobile phone, and has no internet access. He writes first in pencil, then types. He uses electricity sparingly, supplemented by solar panels, and his writing studio is without electricity. He walks the talk, living a life rooted—quite literally—in the land. Thoreau would have approved.

An iconoclast, Berry remains well worth reading. Growth, he reminds us, is not synonymous with the earth’s welfare. Economies, like soils, can be exhausted. Big government and industrial systems, he argues, erode local responsibility, foster dependency, and inflame military and international tensions. Rural poverty in places like Appalachia persists, in his view, because urban prosperity has been purchased by the plundering of these regions.

In 2013, President Barack Obama awarded Berry the National Humanities Medal.

In 2015, he became the first living writer inducted into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame.

That same year, the Library of America published a boxed set of his work—an honor accorded to only two living American writers at the time.

Berry may be impractical. He may be impossible to scale. But he leaves us with an uncomfortable and necessary reminder: care, once abandoned, is not easily restored—and neither are the land, the culture, nor the communities that depend upon it.

—rj