I have always liked poetry and poets, in particular, because of their sensitivity to human experience.

I have always liked poetry and poets, in particular, because of their sensitivity to human experience.

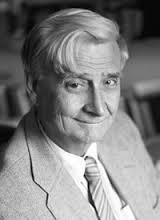

One poet I like a lot is Donald Hall, a giant among contemporary American poets, although he’s given up the craft, or as he puts it, since “poetry abandoned him.”

Hall is now 85.

Let me assure you, while the tropes may not come as easily as before, his acuity remains vibrant in his newest book, Essays After Eighty, a slim volume of 120 pages, yet filled with reminiscence, keen observation, and sober wisdom.

I first got introduced to Hall by way of his textbook, Writing Well, which I used for a number of years in teaching college composition. The book lived up to its title, emphasizing sentence clarity and how to achieve it, with eloquence added in.

Hall has always been a diligent stylist, whether writing poetry or prose. He confesses that he’s written some individual essay drafts for Essays After Eighty upwards of eighty times to get things said right.

I used to tell my students that the name of the game in all good writing lay in revision, pointing out that scholars have come upon nearly fifty drafts of Yeat’s famed “Second Coming” poem.

I like how Hall says it: “The greatest pleasure in writing is rewriting. My early drafts are always wretched.”

I’ve always held that a good style is etched by its economy, the right words sufficing for empty fillers drowning readers in verbosity; a pleasing rhythm like waves, in and out, upon a sea shore.

Good prose, like poetry, runs lean.

And Hall is the great master.

Let me give you a sampling of Hall’s trademark writing acumen, simple, yet keen with observation, each detail chosen well, verbs especially, accumulating into a verbal, painting, reflecting the ethos of a skilled artisan:

In spring, when the feeder is down, stowed away in the toolshed until October, I watch the fat robins come back, bluejays that harass them, warblers, red-winged blackbirds, thrushes, orioles. Mourning doves crouch in the grass, nibbling seeds. A robin returns each year to refurbish her nest after the wintry ravage. She adds new straw, twigs and lint. Soon enough she lays eggs, sets on them with short excursions for food, then tends to three or four small beaks that open for her scavenging. Before long, the infants stand, spread and clench their wings, peer at their surroundings, and fly away. I cherish them….

Reminiscence weighs heavily upon these essays, not surprising for a writer in his mid-eighties. the ghosts, as it were, looming out of the past–grandparents, Mom and Dad, aunts and uncles, friends; wife Jane Kenyon, the love of his life and fellow poet, succumbing unexpectedly to cancer at age 47.

Even the northern New Hampshire topography has yielded to change, farms giving way to rebirth of forest as the new generation migrates to the prosperous cities of southern New Hampshire.

As I read this moving collection of personal reflections on sundry topics, I made sure to highlight a number of striking passages, and some of them I’ll share with you.

On writing:

As I work on clauses and commas, I understand that rhythm and cadence have little to do with import, but they should carry the reader on a pleasurable journey.

If the essay doesn’t include contraries, however small they be, the essay fails.

Nine-tenths of the poets who win prizes and praises, who are applauded the most, who are treated everywhere like emperors–or like statues of emperors–will go unread in thirty years.

I count it an honor that in 1975 I gave up lifetime tenure, medical expenses, and a pension in exchange for forty joyous years of freelance writing.

I expect my immortality to expire five minutes after my funeral. Literature is a zero-sum game. One poet revives; another gets deader.

On aging:

When I limped into my eighties, my readings altered, as everything did.

In the past I was advised to live in the moment. Now what else can I do.?

On leisure:

Everyone who concentrates all day, in the evening needs to let the half-wit out for a walk.

On mortality:

It is sensible of me to realize that I will die one of these days. I will not pass away.

At some time in my seventies, death stopped being interesting. I no longer checked out ages in obituaries.

These days most old people die in profit-making dormitories. Their loving sons and daughters are busy and don’t want to forgo the routine of their lives.

Essays After Eighty has been a wonderful read for me with its acerbic wit, cogent wisdom, delivered in a simple, yet elegant, style, proving again that the best art conceals itself.

And yet there’s a melancholy that haunts these excursions into reminiscence, a sense that the best is over and, now, there’s just the waiting. As Hall confesses, “My problem isn’t death, but old age.”

Hall, of course, is addressing physical decline with its imposed limitations and dreaded dependency; but surely his words resonate still more–the sense of ephemerality that mocks our labors and brings to an end all that we love most dearly.

For Hall, “There are no happy endings, because if things are happy, they have not ended.”

Still, this work, perhaps his last, formulates a testimony to a life lived well.

And, very rarely, do you find such honest telling.

–rj