There exist those books you wish wouldn’t end. Carl Safina’s Alfie and Me: What Owls Know and Humans Think was that kind of book for me.

I had read Safina’s excellent View from Lazy Point several years ago, impressed with its detailed oberservations of wildlife and an arctic indigenous community across four seasons. That same concern for indigenous well-being and the plight of animals in a changing world continue with Alfie and Me.

Safina, a widely published ecological author and Endowed Professor of Nature and Humanity at Stony Brook University, is an expert in marine biology and recipient of many honors, including a MacArthur Fellowship, sometimes dubbed “the genius grant.”

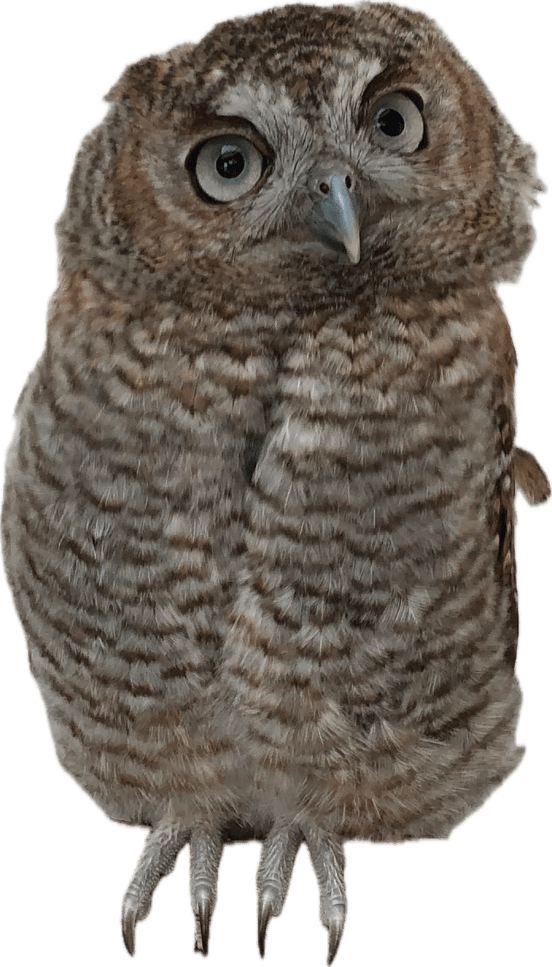

In all his writings, Safina’s focus is on how humans relate to nature, a theme manifestly central to Alfie and Me, chronicling the story of an orphaned Eastern screech owl found in Safina’s Long Island backyard in 2018. Over the course of eighteen months, Safina and his wife, Patricia, nurtured the owl—whom they named Alfie—until her eventual release, creating a rare, intimate portrait of interspecies connection and nature’s resilience.

Safina becomes nearly a helicopter parent, monitoring Alfie’s daily development, torn between fostering her independence and protecting her from the harsh realities of the wild: “… I knew—as she did not—the relative meaninglessness of a life without risks.” An estimated two thirds of young screech hours die shortly after leaving their parents’s nest.

I found myself anxious for Alfie’s survival. Would she learn to fly, to hunt, to mate? Could she survive storms, drought, and the many predators that lurk in her world?

Species survival today depends not only on healthy ecosystems, but increasingly on humans recognizing their relationship with nature as essential to mutual survival.

Safina criticizes Western philosophy for severing this connection, beginning with Plato’s split between the material and spiritual worlds—deeming the material inferior and ultimately fueling nature’s exploitation: “Plato and his followers were perhaps the first people to feel revulsion toward the world. By forever separating our material world from the realm of perfection, Plato propounded a stark dualist doctrine,” Safina says.

For Safina, “This might be the most consequential idea in the history of human thought, its implications almost literally Earth-shattering. Most fundamentally, we are left with: an existence at odds with itself.”

Descartes and Bacon subsequently embodied a modern mechanistic view of nature, oblivious to nature’s sanctity and evolutionary intelligence, leading to its objectification. “The great blindness of the West is to grope the world as inventory,” Safina writes.

In contrast, Safina draws richly from Eastern traditions, which emphasize the unity of all life and the reverence owed to the source from which we came. Although his book is replete with references to Hindu, Buddhist, and Taoist thought, he finds Confucianism especially compelling for its focus on relationships.

Safina also turns to Indigenous cultures as contemporary models of living in harmony with nature. Their ways often involve mindful observation and sustainable stewardship rooted in mutual respect: “For most of human history, Native peoples, more intimate with their existence than we with ours, perceived that Life and the cosmos are mainly relational,” Safina says.

Reading Alfie and Me, I couldn’t help but think of the estimated one billion birds projected to die globally in 2025. According to the Audubon Society, North America alone has lost 25% of its bird population since 1970—about 3 billion birds. Contributing factors include climate change, deforestation, pesticides, habitat destruction, urban structures, insect decline, and free-roaming cats.

Safina’s book appeared in 2023, or before the current avian flu outbreak, which over the past 18 months has led to the confirmed deaths of millions of wild birds in North America—many of them common backyard visitors. The virus has now reached poultry as well, despite the culling of over 166 million birds. A future in which birds no longer sing at sunrise, once unthinkable, now feels disturbingly plausible.

This avian decline is largely human-made, driven by an economy that prioritizes profit over preservation

Why write about birds, some might ask. Shouldn’t human needs come first?

Safina answers with the words of Catholic monk Thomas Merton: “Someone will say you worry about birds: why not worry about people? I worry about both birds and people. … It is all part of the same sickness, and it all hangs together.”

Alfie and Me is not only a poignant narrative about an orphaned owl, but also a powerful meditation on our shared existence, affirming Safina’s truth: “that no isolated separation is possible. We are participant members in one existence—of life, of the cosmos, of time.”

–rj