I remember it well. I was a young graduate student, privileged to study under one of the world’s foremost professors of Victorian literature, a renowned authority on Thomas Hardy.

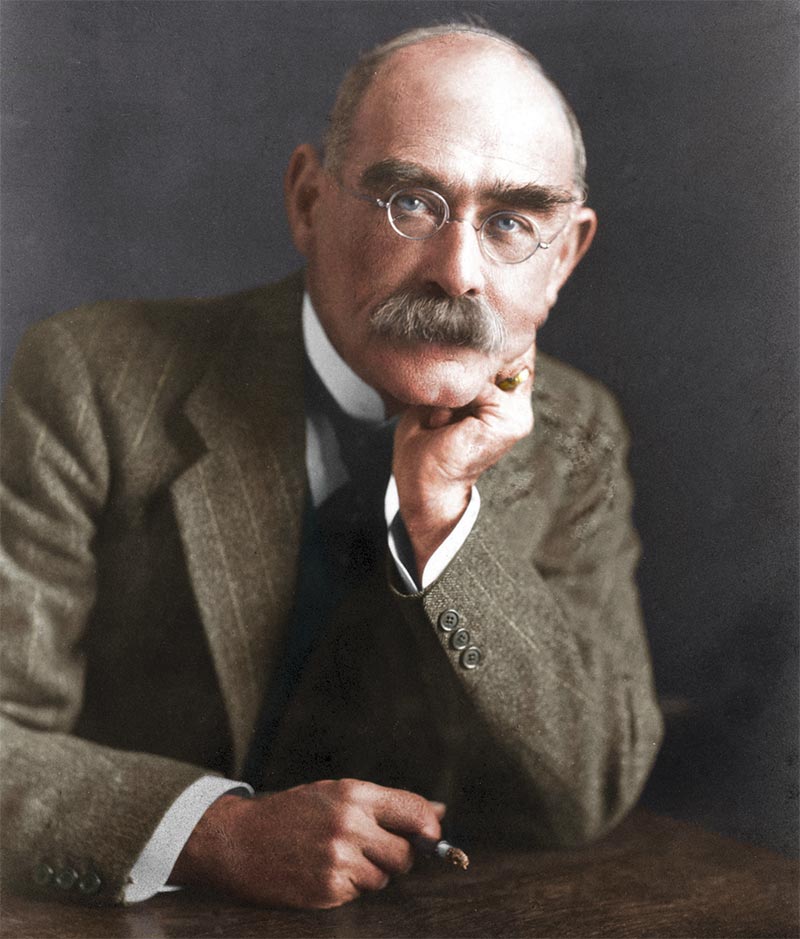

The course was rigorous. We read the greats of the age—Macaulay, Tennyson, Browning, Dickens, Mill, Newman, Arnold, Morris, Ruskin, the Rossettis, Swinburne, Hopkins, Pater, and of course Hardy. Yet strikingly absent was Rudyard Kipling. Our professor dismissed him as the mere voice of imperialist Britain—an attitude then dominant in the Academy, and one I suspect still lingers on American university campuses.

I had never read Kipling. I had not yet learned to question. I accepted what I was told.

It was only later, during a summer course at Exeter College, Oxford, that I encountered another view: one that esteemed Kipling’s literary brilliance without committing the American folly of conflating his politics with the merits of his artistry.

Kipling’s literary range was astonishing. His verse, endowed with rhythmic command, borders on the hypnotic. He opened poetry to colloquial speech and became a supreme craftsman of the ballad form.

Yes, he gave voice to Empire in works like The White Man’s Burden, Kim, and The Jungle Books. But he also revered Indian culture—its spirituality, wisdom, and sensory richness. Often, with subtle irony, he questioned the very order he seemed to affirm.

Perhaps his greatest achievement lies in the short story. With precision and nuance, he crafted narratives of extraordinary compression, modern in their suggestiveness, wide-ranging in their scope. The Man Who Would Be King remains a masterpiece—its sweep and power undiminished. Kipling’s influence on Conrad, Maugham, Hemingway, Borges, and others is beyond doubt.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1907—the first English-language writer to receive it—honored for his “power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas, and remarkable talent for narration.”

Kipling’s stories, like all enduring art, probe psychological depths. They are complex, skeptical of conventional wisdom, and riveting in their precision.

In today’s multicultural Britain, he is taught in context: his genius as a storyteller acknowledged, his colonial perspective rejected. Lewis, Tolkien, and Pullman have recognized him as a precursor to modern fantasy.

In India, where he was born and spent his early years, his reception is understandably ambivalent: many readers disdaining his imperial condescension, yet acknowledging his literary craftsmanship. Salman Rushdie has called Kim “one of the greatest novels written about India,.” Other Indian writers continue where Kipling left off, offering vivid vignettes of India, but through an Indian prism.

Controversy about his place in the Western literary canon remains. Vladimir Nabokov, in his Cornell lectures, dismissed Kipling for his moralizing, He deemed his indulgence in exotic adventure stories as juvenile. Great literature, he argued, obeys the aesthetic imperative of narrative neutrality, or distance, as in Flaubert and Joyce.

On the other hand, the late eminent Yale critic Harold Bloom came to Kipling’s defense. In his The Western Canon. Bloom lists Kipling among hundreds of writers deserving inclusion in the canon. Bloom saw Kipling as a myth maker and gifted story teller, especially in his short stories. On the other hand, he found his poetry “scarcely bear reading.”

While I find merit in both Nabokov’s and Bloom’s arguments, I lean towards Bloom’s appraisal as more balanced. I have long resisted either/or equations, particularly as to the political or aesthetic. Over a lifetime, I have frequently found reasoned judgment occupies a middle place. I have given my own arguments earlier in this essay for his belonging in the canon.

Whatever a reader’s verdict, Kipling was a singular voice, very much his own man. In short, authentic. As he said in an interview shortly before his death,

“The individual has always had to struggle to keep from being overwhelmed by the tribe. To be your own man is a hard business. If you try it, you’ll be lonely often, and sometimes frightened. But no price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself” (Qtd. in the Kipling Journal, June 1967).

rj

The Guardian (July 4, 2017) features a review of a favorite poet of mine, Philip Larkin, in connection with a current exhibit of Larkin artifacts at Hull’s Brynmore Jones Library, where he was a librarian for many years.

The Guardian (July 4, 2017) features a review of a favorite poet of mine, Philip Larkin, in connection with a current exhibit of Larkin artifacts at Hull’s Brynmore Jones Library, where he was a librarian for many years.