D.G. Chapman, Upsplash

Silence has always allured me, most often when it is bound to expanses empty of people—though not always. I can find it just as readily in a library, or even in my own home when left to myself.

It is not, I believe, a resistance to an oppressive environment—work, academics, trauma, peer pressure, or the quotidian churn of human caprice—what psychiatry terms “psychological reactance.” It goes deeper than that, perhaps rooted in my introversion, which inclines me away from crowds and constant social encounter.

I carry memories of three landscapes that produced instant rapture: a sense of detachment, of absence from time itself—something larger than me, and yet intimately felt.

The first occurred when I was a graduate student in North Carolina, visiting the hillside at Kitty Hawk where the Wright brothers first achieved sustained flight in their ungainly aerial contraption. I had gone with friends, who wandered along the beachfront below, leaving me alone atop the hill. There, history seemed to recede. The wind moved through the grass, the sky stretched open and unmarked, and for a moment the present dissolved, as though time itself had paused in reverence.

Then there was Arlington National Cemetery, its vast rows of symmetrical white grave markers extending beyond easy comprehension. The stillness there was not empty but weighted, a silence shaped by collective sacrifice. For a brief moment, the eternal peace of America’s fallen became my own.

Most memorable of all were Scotland’s Highlands. Driving eastward from Edinburgh, they rose suddenly and unexpectedly across the horizon—rugged, green, and seemingly untouched by human intrusion. I pulled over, stepped out, tested the firmness of their verdure beneath my feet, and listened to what I can only call their shouting silence. That moment remains my most cherished travel memory.

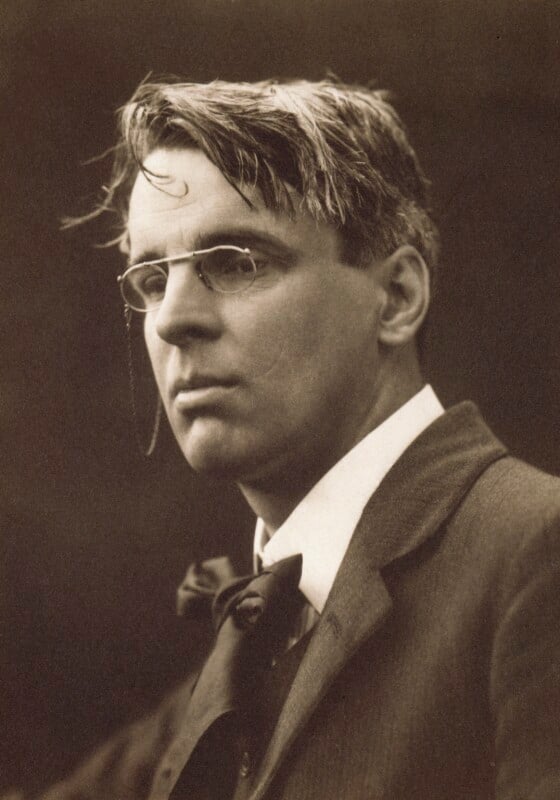

As an English major in college, I once took a course devoted entirely to Wordsworth—England’s great poet of landscape. I am, perhaps, a rarity in having read all of his several hundred poems. Among them, “Tintern Abbey” most fully captures my response to those landscapes:

“…that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,—

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul…”

Literary scholars describe this response under the notion of the sublime: the experience of being overwhelmed through intimacy with nature, a flash of clarity in which one intuits a larger coherence behind nature’s mystery. Wordsworth gives it further voice:

“And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man….”

Psychology approaches the experience from another angle. One theory frames it as a sensory reset—the mind’s need to unburden itself from obligation and affliction, a release from the cognitive overload of daily life.

I am especially drawn to E. O. Wilson’s Biophilia Hypothesis, which proposes that humans evolved in constant contact with nature, calibrating the nervous system through millennia of hunter-gatherer life. In that context, a deserted landscape could signal safety—the absence of predators, permission to rest.

Another perspective, the Default Mode Network, suggests that quiet environments can trigger awe by suspending habitual rumination. Freed from constant external demands, the mind drifts toward reflection, memory, and imaginative connection. In such moments, the brain is allowed to hear the rhythms it evolved to monitor.

This makes intuitive sense. We live in a world saturated with anthropophonic noise—human-made sound without pause or mercy. Though nature is never truly silent—wind, water, and the subtle movements of life persist—these sounds soothe rather than assault. They restore rather than demand.

Wordsworth seems to anticipate this longing even in the heart of the city. In “Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802,” he finds London redeemed by a rare moment of stillness:

“Earth has not any thing to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne’er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!”

Perhaps silence, then, is not an absence but a presence—one that returns us to ourselves, quiets the mind’s noise, and restores a way of listening we once possessed, and have not entirely forgotten.