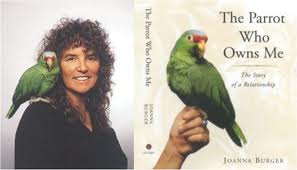

I’ve just finished Joanna Burger’s The Parrot That Owns Me: The Story of a Relationship. Funny, I had this book sitting on my shelf, unread, for twelve years. Looking for something to read while eating my breakfast, I pulled it down and started what turned out to be a fun read.

I also learned a great deal about birds and, especially about parrots, surely one of the most intelligent of animal species, though we normally think of primates (gorillas, chimps, orangutans, etc.), dolphins, elephants and pigs as honorary Mensa candidates among our animal kin.

Burger, one of the world’s leading ornithologists and Rutgers University prof with over twenty books to her credit, tells how Tiko, her Red-lored Amazon, practices a repertoire of tonal warnings to distinguish varied predators, most notably, hawks, cats, and snakes.

She writes that “when Tiko gave his hawk call, Mike (her husband) and I would invariably spot a Red-tailed, Sharp-shinned, or Cooper’s Hawk flying overhead or perched in a nearby tree. Tiko’s response was so consistent that there was no question that he recognized hawkdom” (167).

Likewise, Tiko doesn’t like snakes, one of which Burger kept for a while, much to Tiko’s dismay. Only when the snake went into hibernation could he be content in the same room.

But how does Tiko pull this off? After all, he seems to possess a genetic memory of jungle predators, even though he’s been totally reared in captivity and has never had any interaction with hawks or snakes?

Years ago I had started reading Jung, who has impressed me more than Freud as being on the mark when its comes to the seminal sources lurking behind human behavior. Jung proposed the theory of archetypes, or “primordial images” (Man and his Symbols, 67), reflecting instinctual urges of unknown origins. They can arise in our consciousness suddenly and anywhere apart from cultural influence or personal experience. Often they take shape in our consciousness through fantasy, symbol, or situational pattern.

And so with Tiko as well as ourselves, the instinctual responses perpetuating survival have become wired in the brains of sentient creatures. Untaught, they’re automatic.

Today, science overwhelmingly confirms the accuracy of Jung’s prescience. Take, for example, the eminent biologist Edward O. Wilson, who attests that monkeys “raised in the laboratory without previous exposure to snakes show the same response to them as those brought in from the wild, though in weaker form (In Search of Nature, 19).

The explanation, of course, lies in evolution’s conferring differential survival value through natural selection. Those who learn to respond to fear quickly simply pass on more of their offspring with their response mechanisms.

Wilson goes further, arguing that human culture itself is considerably biological in origin, or genetically prescribed, supported by analytical models (123-24).

A Jungian at heart, I found Tiko’s innate capacity to respond to elements of danger another in a long line of evidence supporting Jung’s pioneering perspective; on this occasion, by way of one of the world’s most astute animal behaviorists, Joanna Burger.

Nature never ceases to amaze me!

–rj