The Somme, the Marne, the several battles at Ypres, Verdun with its prolonged agony, this was World War I enmeshed in its trench warfare, stalemated armies, and colossal slaughter on a massive scale impacting five continents

Next year marks the centennial of the outbreak of World War I, for many years known as the Great War in which an estimated 10 million combatants perished along with many civilians. While you don’t see much, if anything in the movies these days about the conflict, as a boy I used to regularly take in films like The Fighting 69th, All Quiet on the Western Front, Sergeant York, and the classic Paths of Glory. Of course there were then many veterans still In their early fifties, boosting demand for such films.

My father, a war veteran with inherited Irish wit, could spin a story that simply wouldn’t lose its hold no matter how many times he told it, of artillery duels; driving an ambulance; the fragility of life with war’s tragedy compounded by the pandemic Spanish flu that would kill millions more. When he died in the VA Hospital he left little apart from a prized heirloom of his hand-completed discharge papers, faded by nearly a century of time, yet still legible, listing his combat participation in France (Argonne sector, 16th Field Artillery, Battalion A). How superbly different from the impersonal DD 202 the military hands out these days. He was proud of his service and lies with fellow soldiers in the veteran’s portion of St. Mary’s Cemetery in Salem, MA.

Early in my teaching career, I came across a student who wanted to focus her research on World War II, which fascinated her. That was fine with me, though I’ve always found the first of these world conflicts more intriguing and compelling. In fact, it made World War II inevitable, given the punitive humiliation imposed by the Versailles Treaty on Germany with its reparation requirements, occupation of the Ruhr, loss of colonies and, in Europe, of German speaking territories (Bohemia and Alsace-Lorraine), thus making a psychopath like Hitler palatable in the wake of the explosive inflation and unemployment that followed.

Certainly, the earlier war vastly changed European and Middle East boundaries with the break-up of the several centuries old Ottoman Empire into Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Kuwait, Jordan and Palestine. It also led to the remarkable founding of modern Israel after a two millennia hiatus and the chronic feud that exists between Israelis and Palestinians, fueling the rebirth of Islamic fundamentalism and spilling over into a world-wide apparatus for terrorism.

In Germany’s obsession to knock out Czarist Russia from the war by creating instability, it smuggled Lenin into Russia, out of which came the Soviet Union with its tyrannous hegemony.

With respect to the events that took place in Kosovo in the 90s and, more recently, with our own incursions into Iraq, it’s clear that World War I has continued its subtle influence. In many ways, the present Middle East ominously resembles the troubled Balkans that led to war.

Certainly, the World War I marked the collapse of an enduring intra-European peace, apart from the 1870 conflict between France and Germany, since Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815. It also decisively terminated the Victorian era that had survived Queen Victoria’s death in 1903 with its moral absolutes and vibrant idealism. Anticipated by Zola and Nietzsche late in the previous century, not only were physical boundaries radically altered, but ideological ones too as a pervasive dissonance took hold following this opening act of strayed technological capability with its attendant horrors applied to the battlefield in the advent of tanks, rapid fire rifles, machine guns, long range artillery, motorized vehicles, submarines and aerial bombing and strafing. Alas, it was at Ypres in early 1915 that the Germans added mustard gas to their arsenal.

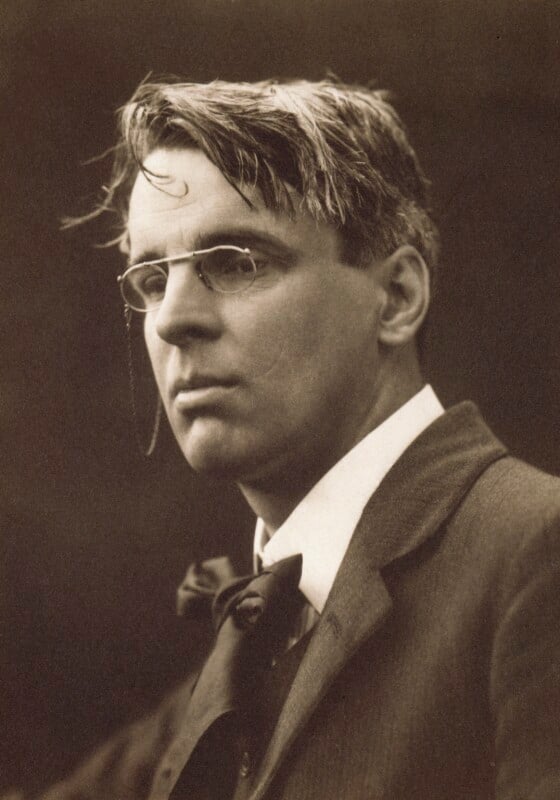

Losses proved staggering with civilians for the first time deliberately targeted. What Auden would later call the “age of anxiety,” had begun, epitomized in the cultural popularity of depth psychiatrists Freud and Jung. Old universals toppled amid an inveterate skepticism filling the vacuum. Culturally it took hold in poems like T. S. Eliot’s nihilistic Waste Land and Yeats’ s still often quoted “The Second Coming” with its annunciation of the apocalyptic of violence and cruelty beyond the precincts of human decency, finding summary cognizance in Joyce’s Ulysses with Stephen Daedalus’s dictum , “History is the nightmare from which I’m trying to awake.” Hemingway would famously call those coming of age during this conflict “the lost generation.”

World War I, as I’ve hinted, was important not only for its immense tragedy that might have been avoided had cooler heads prevailed over charged nationalism, but because it proffered prescient warnings to our own generation. As Oxford historian Margaret Mullins reminds us in her NYT op ed, “The Great War’s Ominous Echoes” (December 13, 2013), our contemporary world milieu manifests many similarities to events just prior to the guns of August 1914:

1. Globalization was taking place then as now, with every portion of the world exponentially linked by rail, steamship, telephone, telegraph and wireless.

2. New ideologies–psychological and political–were underway, including fascism and communism. Science, too, had begun its explosive advances that saw Einstein develop his theory of relativity.

3. With widening access to information and know-how, that time was also replete with terrorism as happened with the assassination of Austrian-Hungarian heir to the throne Archduke Ferdinand along with his wife by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo (Bosnia). In America, President McKinley was murdered by an anarchist. In the world at large, railways were continually under bomb attack. Today that ability of technology to level the playing field through the Internet and social media has multiplied many fold and is thus suffused with even more danger as places of gathering.

4. Then as now, key mistakes were being made as to the changing methodology of contemporary warfare. In our own time, surgical strikes and carpet bombing may no longer apply to obtaining a maximum result in a brief interval, as the paradigm has shifted to less visible targets who, in fact, may not even be there, having left their residue as an IED. Moreover, the horror of civilian casualties often inflicted by aircraft, including drones, is now subject to instant playback in the media and social networks, leading to vigorous demands to cease

5. Then, as now, rivalries were underway as new powers sought parity: Germany with Britain; today, China with the U. S. Growth of a rising economic power, unfortunately, can often translate into military prowess as with Germany and currently, China. New coalitions mustering around key antagonists are once again taking shape as China moves to challenge America’s Pacific presence. Accordingly, the dangers of an incendiary mistake become all too possible.

It’s been said that history repeats itself. I hope not.

–rj