Existence exerts a randomness in its distribution of fate. The wicked, as Job tells us, often live long, escaping their misdeeds with impunity; the just and talented, curtailed lives amid their greatest promise.

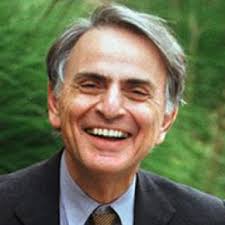

The list of those I deem the “righteous,” those who’ve especially influenced who I am, the values I embrace, and my hopes for a better human future taken from us early, their age at death indicated in parentheses, includes Princeton sage Walter Kaufman (59), biologist Stephen Jay Gould (62), astronomer Carl Sagan (62), science fiction writer Octavia Butler (58), essayist and novelist George Orwell (46), political sage and philosopher John Stewart Mill (66), and, not least, poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (44).

I’m tempted to write a series of extended separate tributes to each of them in Brimmings, but will limit my commentary for now.

I was in my early twenties. a college student just out of the military, when I somehow came upon Walter Kaufmann’s The Faith of a Heretic (1961), which I’m re-reading now. He was the first to admonish me to accept only the empirical in the quest to discern the probable, to find courage to change course, and live daringly: “The question is not whether one has doubts, but whether one is honest about them.”

Evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould impressed me early with his clear cutting, scintillating prose endowed with grace, teaching me that science is not simply pursuing the factual, but a way of thinking that enlarges one’s humanity. Life is by-product of chance and contingency: “Human beings arose, rather, as a consequence of thousands of linked events, none of which foresaw the future.”

Astronomer Carl Sagan demanded the imprimatur of evidence for any accepted belief. Rationality demands we not cloister ourselves in cultural hand downs—that extraordinary beliefs merit skepticism: Compromising truth invites demagoguery and superstition’s advance: “We make our world significant by the courage of our questions and the depth of our answers.”

African-American Octavia Butler has been a remarkable recent read, writing eleven science fiction novel standouts resonating urgency in confronting systemic collapse of ecosystems consequent with climate change. Her Parable of the Sower, a must read, has proven chillingly prescient. Change is life’s inevitability, morally indifferent, demanding adaptability to survive: “Human beings fear difference, and they fear it so deeply that they will not only oppress but destroy what they see as different.”

George Orwell, well known for his clairvoyant 1984, has always impressed me with the clarity of his writing, achieved through disciplined study; his wariness of manipulative despotism and its verbal deceit stratagems such as ’doublespeak,” timely and precise in their warnings of euphemism and abstraction: “Political language… is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.”

John Stewart Mill, “the saint of rationalism,” remains a seminal influence, ahead of his time, a champion of classical liberalism and its advocacy of the minority’s right to dissent. He taught me about nature’s indifference and logic’s necessity in a world absent of revelation. I return to him repeatedly for wisdom and inspiration: “If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.”

Gerard Manley Hopkins has long been my most esteemed poet with his vibrant “sprung rhythm,” latent with emotion, a passion for nature and for those who suffer—so many—life’s inequities. His poetry sings, reenacting experience via the sensory, capturing the essence of all things. As a Jesuit priest, while not resolving the problem of suffering by resorting to a cozy theodicy or relying on sentimentality, he helps render its endurance: ‘I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.”

I am forever grateful for their stalwart witness to life’s truths. Their lives argue by example rather than system—that meaning isn’t guaranteed by justice, nor extinguished by its absence. Fate distributes arbitrarily; conscience does not.

—rj

Ithaca, New York, at the southern end of Cayuga Lake, is a progressive town of about 30,000 people and hub to one of the state´s prettiest areas of undulating rural greenery, consisting of vineyards, apple orchards, pastoral farms and scattered water bodies known as the Finger Lakes.

Ithaca, New York, at the southern end of Cayuga Lake, is a progressive town of about 30,000 people and hub to one of the state´s prettiest areas of undulating rural greenery, consisting of vineyards, apple orchards, pastoral farms and scattered water bodies known as the Finger Lakes.