I took up reading Irish literary sensation Sally Rooney to find out what the fuss was all about. After all, she’s only twenty-eight and has written two novels that have rocked the literary world, Conversations with Friends (2017) and Normal People (2018), dubbing her the gatekeeper of the millennial generation. Saying you’ve read Rooney is the new chic.

Where does such youthful sagacity come from, that sureness of stroke distilled in cerebral awareness of the ambiguity, especially defining relationships, of society’s cultural constructs, social, political, and economic? Adding to the enigma, why attempt sorting out others, when we’re a mystery to ourselves as her characters abundantly demonstrate?

Rooney is a graduate of prestigious Trinity College, which becomes the principal foreground of Normal People. Its graduates include luminaries like Bram Stoker, George Berkeley, Edmund Burke, Samuel Beckett, Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift, William Trevor and Mary Robinson. Rooney received a master’s degree from Trinity in American literature.

She has the smarts. No one doubts that. As for her two novels, if you’re into politics, especially the progressive kind, you’ll rollick to their beat, both novels pounding the political turf with trendy leftisms, fashioned in the aftermath of the market collapse of the Celtic tiger economy in 2008 and Rooney’s own upbringing in a Marxist household. Good novelists are inevitably iconoclasts and Rooney’s two novels, love stories, don’t disappoint in this regard. The question is how well she succeeds.

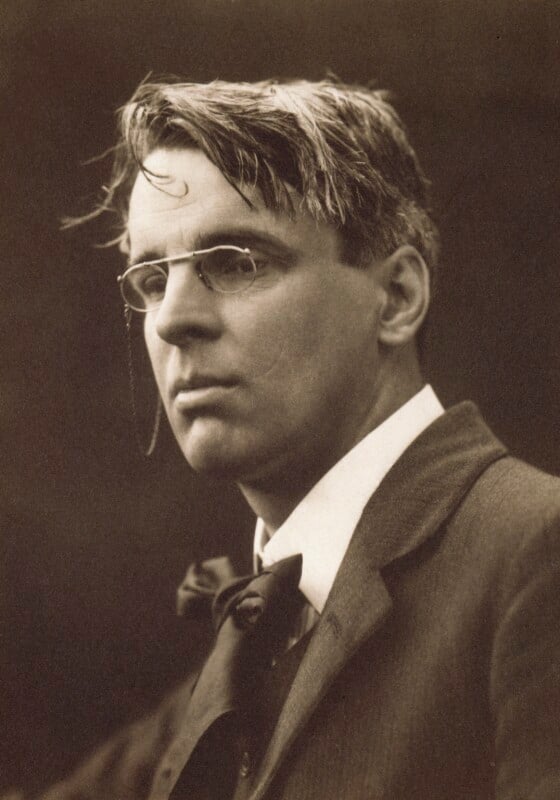

Conversations with Friends is narrated in first person by Frances, a bisexual communist in love with a married man, Nick, in a dysfunctional marriage. Her political sentiments come early and uncompromisingly when confessing to Nick that she had sex recently with a guy she met on Tinder, an admirer of Yeats, whom she earlier dismisses as fascist: “No one who likes Yeats is capable of human intimacy.”

Wage inequity arises in Conversations and discourages Frances from seeking work, a sentiment shared by many unemployed or under-emplored millennials these days:

I had no plans as to my future financial sustainability: I never wanted to earn money for doing anything. […] I’d felt that my disinterest in wealth was ideologically healthy. I’d checked what the average yearly income would be if the gross world product were evenly divided among everyone, and according to Wikipedia it would be $16,100. I saw no reason, political or financial, ever to make more money than that.

In Normal People, both Connell and Marianne worry about employment, even though they’re academically achieving university students. Marianne is unfailing in dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s in her ripostes of leftist student platitudes.

Marianne comes from a well-situated family; Connell, from a working class, single mother household. Class dialectic underlines a fundamental tension between the two, save there’s no genuine synthesis, despite their mutual love.

Connell’s mother is a housecleaner in Marianne’s parents’ upscale home. Ironically, she’s a disillusioned socialist, who undermines with laughter Connell’s recent enthusiasm for a local communist candidate:

Come on now, comrade, she said. I was the one who raised you with your good socialist values, remember?

Connell texts the disappointing election results of Fine Gael’s victory to Marianne who replies, “The Party of Franco,” alluding to the sending of a brigade of 700 combatants supporting the Nationalists in Spain’s civil war, despite the party’s official neutrality status. Connell has to look up the history. Rooney has a history of never letting her Leftist orthodoxy tolerate perceived apostasy.

Although sex is paramount in both novels, replete with minutiae and underscore’s women’s sexuality and love, it pervasively mutates into pathology, or power constructs, contributing little to promoting where the narratives should be headed—the social interchanges with others that comprise our identities and potential for self-realization. In relationships of disparity, subordinates, like Frances or Marianne, may utilize sex to approximate getting what they want, but cannot have. So much of this comes down to, Am I worthy of love? Replete with self-analysis as provender of self-mastery, it sputters into repetitive ineffectuality.

If anything, sex in these novels mirrors momentary catharsis, not sequels of emancipation from social, or class, determinants. Except for Bonni, in Conversations with Friends, the characters would do well with a bit of professional counseling. Supposedly in love but enmeshed in self-interest, characters in both novels emotionally engage in mutual tug of war.

Psychologically, Conversations with Friends and Normal People exhibit all the trademarks of co-dependency. Nick and wife, Melissa, for all their mutual infidelity, will not abandon their marriage. Nick, not incidentally, suffers from chronic depression and has been an in-patient at a psychiatric hospital. Marianne engages in self-injury behavior, symptomatic of deep-seated anxiety and self-loathing. Similarly, she hooks-up with a BDSM artist while a student in Sweden. In one scene, she wants Connell to throw her out of bed. Connell lacks self-confidence and resembles Nick in his depression. Rooney foreshadows in Conversations the self-inflicted masochism we see in Normal People, Frances ruminating about Nick, “I wanted him to be cruel now, because I deserved it. I wanted him to say the most vicious things he could think of, or shake me until I couldn’t breathe.”

But let’s talk about the writing itself. Both novels are like Twitter exchanges rather than vibrant telling. Language seems almost an intrusion in the short, blunt dialogue that frequently consists of text messaging and emails absent of punctuation and capitalization, not atypical of millennials. Quotation marks never occur in these novels to demarcate speakers, a mannerism serving no purposeful function other than an underlying contrariness that earmarks her essays and interviews. Normal People meanders into cliches, and not very good ones at that.

Absent of artifice, devoid of symbol or pattern, these novels read more more like sociology texts, laconic and, worse, so continuous, they provide no real climax or meaningful denouement leading to resolution. Despite the politics, there’s no genuine revolt and we end in stasis, or where we began. At Normal People’s end, Connell still waxes control, with Marianne’s validation dependent on his acceptance in what seems a rushed ending. You’ve got oppression without liberation. Sadly, both Frances and Marianne are non-assertive women in symbiotic relationships. There are no breakthroughs.

Whether these two novels merit their accolades, they do mirror the lifestyle of many millennials today, less sure of their futures than their parents were, rebellious against traditional mores, steeped in social media, while religiously and politically cynical. Both novels are trendy, but is this enough?

Out of curiosity, I wandered over to Goodreads to view reader reactions. While Rooney has her coterie of enthusiasts, a fair number complained of a dullness in plot and characters fundamentally unhinged who you’d not like rubbing shoulders with in everyday life.

Having read both novels, I’ve gone on to reading Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lac, a Booker Prize winning novel. No contest with lines such as “That sun, that light had faded, and she had faded with them. Now she was as grey as the season itself.” For me, Brookner wins hands down for insight, delivery, and relevance in depicting women’s efforts at finding emancipation in a patriarchal culture. Or as one critic put it long ago, “She makes some writers look a bit unsheveled and a little vulgar” (Rosemary Dinnage).

I think, too, of Edna O’Brien, Ireland’s preeminent feminist novelist hailing, like Rooney, from west Ireland and still writing at nearly ninety on similar themes of women’s internal lives, meriting a comparison to gain Rooney’s full measure, despite the generational divide. Like Rooney, she captured the essence of a new generation of women. In her formulae for writing, O’Brien comments, “Everything is very important – the landscape, the story, the character – but the rhythm and musicality and the spell of language, that’s what it is. Otherwise you’d put it on a postcard” (Irish Times, Nov. 7, 2015). I wish Rooney had taken note.

I like to think we really need something like fifty years to objectively validate a novel and, say, judge it a classic. Will posterity still read Hotel du Lac come fifty years? I’d wager yes. Not so for Conversations With Friends or Normal People.

We’d do better to heed critic Harold Rosenberg’s observation about generational thinking: “Except as a primitive means of telling time, generations are not a serious category. The opinions of a generation never amount to more than fashion. In any case, belonging to a generation is one of the lowest forms of solidarity.”

–rj