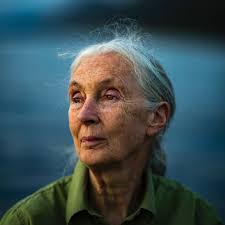

It’s with profound sadness I learned yesterday of primatologist Jane Goodall’s death at age 91.

Blessed with remarkable genes, she lived life with zest up to the very last, tirelessly traveling across international landscapes to raise funds for her Jane Goodall Institute in Tanzania, founded in 1977.

I read her NY Times obituary, but it falls short in evaluating the plenitude of her achievement and its significance for all of us. I learned some time ago that the NYT composes many of its obituaries in advance, ready-to-go like a frozen pizza.

It doesn’t take into account her devotion to the Tanzanians among whom she worked for sixty years, as earnest for their welfare as she was for chimpanzees, humanity’s closest relatives, possessed like us with dual capacity for good and evil.

She gave early warning of climate change as an eyewitness of its exponential ravages in Africa, the front line of its advance.

You can learn much of what she accomplished through reading among her many books The Shadow of Man or A Reason for Hope of her work in Africa, breakthroughs in science, and personal beliefs, some of them controversial such as her advocacy of birth control availability to help African families limit their family size. Tanzania is second among Africa’s 54 nations in population growth. With a present population of 68 million, its projected 2100 population will swell to 283 million, imperiling its subsistence resources.

Goodall had faced an uphill climb in winning acceptance among male scientists, stubbornly suspicious of any woman’s achievement in investigative research. Initially, when setting out for Africa, she had been a waitress and secretary. A wealthy donor, however, recognizing her brilliance, provided the funding for a Ph.D. in ethology at Cambridge University, Goodall one of the rare individuals to directly achieve a Ph. D., not having been an undergraduate.

I confess to a personal attachment to Goodall who, like me, suffered from lifelong prosopagnosia, a neurological disorder inhibiting one’s ability to recognize faces.

Currently the fate of her African investment, employing thousands of Tanzanians, remains under unrelenting threat with population growth, agricultural expansion, deforestation, fragmented forest, habitat loss, logging, and lack of consistent government enforcement of land use laws; not least, the volatility of donor contributions on which the work depends, collectively posing a Sword of Damocles hovering over its future.

There remain just 2300 chimpanzees throughout Tanzania, with an estimated 90 to 100 in Gombe National Park, the site of her research. Those numbers are down from the original 150 as elsewhere in Tanzania, bush meat remains a frequent staple despite its health risks. AIDS had its origin in Africa, consequent with eating chimpanzees harboring the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV). Goodall was a committed vegan, ardently opposed to factory farming.

Also contributing to their demise is ever expanding human encroachment.

A friend of animals, champion of Mother Earth, always with passion and never without hope, Dr. Goodall is in my pantheon of heroes, her many awards including the Presidential Medal of Freedom (USA), the Steven Hawking Medal of Science for Communication, and designation as Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE).

Acknowledging her advanced age, she approached death as her “next great adventure. When you die, there’s either nothing, it’s the end, or there’s something. And things have happened to me in my life that I feel there is something. And if there is, I can’t think of a greater adventure than dying.”

I wish I lived in a world which lowered its flags in tribute to Dr. Goodall:

”Somehow we might keep hope alive—a hope we can find a way to alleviate poverty, assuage anger, and live in harmony with the environment, with animals, and with each other,” she wrote.

A candle has gone out and I feel lonely and in a dark place.

rj