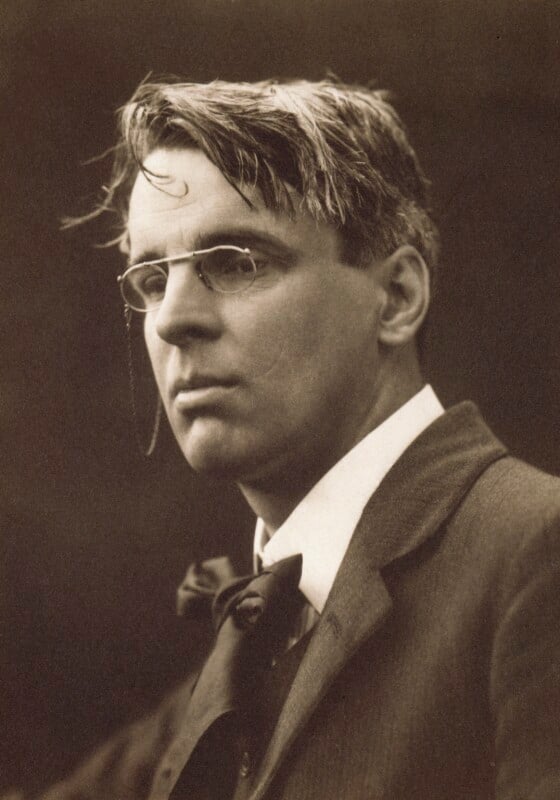

I’ve always been a devotee of the poetry of William Butler Yeats, though not of his metaphysics or his politics. Certainly, his reception in Ireland over the years has been bleak, the latest hostile critic, contemporary novelist Sally Rooney piling on, dismissing his politics as fascist, with the takeaway he isn’t worth reading.

Though he flirted with authoritarianism, agitated by the chaos he associated with democracy, he supported the Free State and later repudiated Mussolini, whom he initially admired. He was never the likes of Ezra Pound. In one of his final poems, “Politics,” he expresses his disillusionment with political ideologies proffering easy remedies for society’s ills.

Yeats should not be judged removed from the convulsions that gave birth to an Ireland free of its English masters.

Ireland’s ostracizing of its literary giants has a long history, not only with Yeats, but James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Frank O’Connor, Sean O’Faoláin, and the late Edna O’Brien, all of whom chose exile.

I bristle against censorship and book banning to which it often leads. Things are changing in Ireland, a nation I know well, but old attitudes can find an audience still.

Yeats remains worth reading, his poetry arguing for itself in its craftsmanship, beauty, and relevance. His often quoted “The Second Coming” hovers over us in its prescient warning of autocracy’s sinister reach.

“A Prayer for My Daughter” remains among my favorite Yeats poems—subdued in tone, subtle in rhythm, redolent in wisdom.

Written in 1919 in the context of Ireland’s incipient nationalism that would spark a civil war and the country’s ultimate partition, the poem expresses Yeats’ hopes for his new daughter in a less turbulent future.

A poem abundant in symbolism, Yeats prays she shun hatreds, value inner over external beauty, find solace in tradition and ceremony.

I value the poem, not least, for its relevance to our own time.

Excerpt:

May she become a flourishing hidden tree

That all her thoughts may like the linnet be,

And have no business but dispensing round

Their magnanimities of sound,

Nor but in merriment begin a chase,

Nor but in merriment a quarrel.

O may she live like some green laurel

Rooted in one dear perpetual place.

My mind, because the minds that I have loved,

The sort of beauty that I have approved,

Prosper but little, has dried up of late,

Yet knows that to be choked with hate

May well be of all evil chances chief.

If there’s no hatred in a mind

Assault and battery of the wind

Can never tear the linnet from the leaf.

An intellectual hatred is the worst,

So let her think opinions are accursed.

Have I not seen the loveliest woman born

Out of the mouth of Plenty’s horn,

Because of her opinionated mind

Barter that horn and every good

By quiet natures understood

For an old bellows full of angry wind?

This last stanza obviously alludes to Maude Gonne, who had become a strident voice of Irish nationalism and to whom Yeats had twice proposed marriage, but was rejected.

In 1990, I was privileged to meet and converse with Anne, the daughter in this poem.

Whatever our views on artists such as Yeats, or antisemite T.S. Eliot, or Chilean fervent communist Pablo Neruda, I subscribe to the autonomy of art. It’s narcissistic to think artists must share our views.

rj