To behold death in the face of this once, he knew there could be no reincarnation, and he thought it a blessing, to have this once to swell forth, then to be enfolded like a seed into the sheltering darkness of eternity — to be lost in time among such furrows as the sea makes (Duffy, The World as I Found It).

When Joyce Carol Oates praised Bruce Duffy’s The World as I Found It (1987) as “one of the five best non-fictional novels,” I knew it would be my next read.

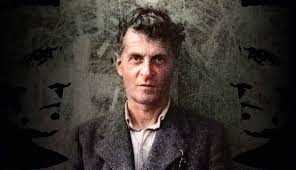

A blend of fact and fiction, it replays the legacy of esteemed philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s complex life, thought, and turbulent relationships with fellow Cambridge contemporaries, Bertrand Russell and G.E. Moore.

Born into a privileged Viennese family of wealth and culture, much of his adult life was impacted by a domineering father, his experience as a combat soldier, frequent retreats from public life, and sustained quest for truth.

Enigmatic, his thinking underwent continuous flux, making Duffy’s achievement quite remarkable.

Duffy didn’t have the resources of extant biographies at the time.

Adding to his challenge was integrating Wittgenstein’s complex thought into his narrative, yet retaining readers unversed in analytical abstraction.

Wittgenstein premised the insufficiency of philosophy in ascertaining reality, its true function one of providing examples subject for further investigation. It mustn’t attempt to usurp science.

The World as I Found It unfolds episodically, interwoven with asides to the three philosophers—their temperaments, perspectives, strengths and weaknesses.

Of the three academic luminaries, Wittgenstein and Russell captivated my interest with their disparate temperaments: Wittgenstein, the youthful upstart; Russell, the widely celebrated academic renowned for his contributions to logic, epistemology, and the philosophy of mathematics.

In contrast, though the elder G.E. Moore, brilliant and benevolent, serves as mediator between the two rivals, his serene domesticity and lack of the same intense character traits, renders him less compelling than Russell, ebullient with conceit, yet haunted by self-doubt and bouts of jealousy, the putative exponent of free love; or Wittgenstein, volatile in temperament, given to barbed tongue directness, unsparing and wounding when critiquing his colleagues’ scholarly endeavors.

Wittgenstein emerges a good man, sincerely seeking life’s meaning and doing the right thing; Russell, in contrast, competitive and self-indulgent.

It appears Wittgenstein underwent some kind of religious conversion during his war years, though not in the conventional sense, perhaps influenced by Tolstoy, whose Gospel in Brief he carried everywhere and could virtually quote from memory.

In fashioning a fictional biography, Duffy made numerous changes not conforming to the biographical facts or timelines:

No letters exist between Wittgenstein and his despotic father.

He assigns Wittgenstein two sisters. He had three.

Wittgenstein never met D. H. Lawrence, despite Bloomsbury’s Lady Ottoline Morrell’s best efforts.

It was Wittgenstein’s excluded sister, Hermine, not Gretl, who sheltered Jews in Nazi occupied Vienna at great personal risk. This anomaly puzzles me.

Then there’s the inimitable, impulsive Max, rough in exterior, potentially violent, yet Wittgenstein’s faithful companion. Duffy confesses in his Epilogue that he never existed, reminding us of the controversy erupting on the book’s publication: Is it ethical to fictionalize historical figures and events, selectively altering character dynamics and outcomes to serve a narrative?

Still, the defining lineaments of Wittgenstein’s life are never distant: the interplay of a controlling father; the family’s wealth and cultural milieu; the several sibling suicides; the cottage built and retreated to in remote Norway; the two years of trench warfare on the Eastern Front in the Great War; the profound influence of Otto Weininger’s Sex and Character; the failed teaching stint in rural Austria; the abandonment of Cambridge; the late sojourn in Ireland and visit to America; the move into his physician’s home as he confronted his fatal prostate cancer. Even his last words, “I have lived a happy life.”

Seldom have I read a book so beautifully written and stylistically riveting, the cadence of its sprawling sentences endowed with verbal exactitude, rendering scenes and personages into palpable visages, an exemplar for aspiring writers.

The New York Review of Books deemed Life as I Found It a classic, restoring its availability in a handsome Classic Series edition, replete with Duffy preface and epilogue.

At its core, The World as I Found It transcends philosophy, embracing the often contradictory lives of those driven to understanding their world.

A narrative about ambition, genius, and the human condition, it offers profound insights into the interplay of intellect, emotion, and morality.

—RJ

Discover more from Brimmings: up from the well

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.